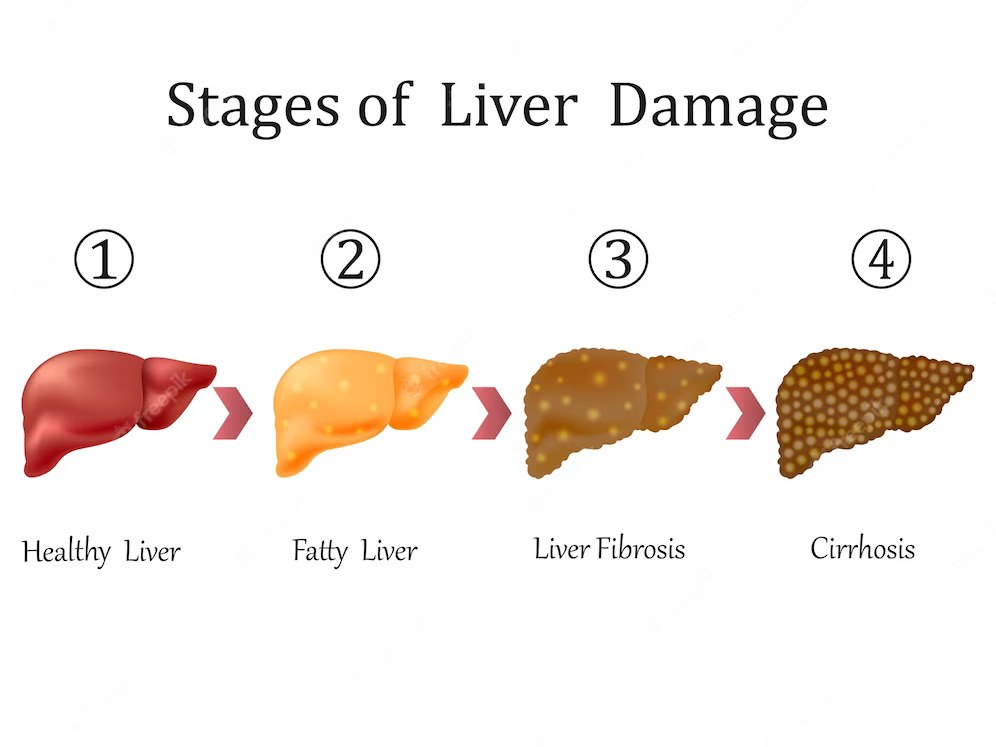

A new study conducted in an animal model at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center showed that fructose rapidly caused liver damage even without weight gain.

High-Fructose Diet Could Lead To Liver Damage

The researchers found that over the six-week study period liver damage more than doubled in the animals fed a high-fructose diet as compared to those in the control group.

“Is a calorie a calorie? Are they all created equal? Based on this study, we would say not,” Kylie Kavanagh, D.V.M., assistant professor of pathology-comparative medicine at Wake Forest Baptist and lead author of the study, said.

In a previous trial which is referenced in the current journal article, Kavanagh’s team studied monkeys who were allowed to eat as much as they wanted of low-fat food with added fructose for seven years, as compared to a control group fed a low-fructose, low-fat diet for the same time period.

Not surprisingly, the animals allowed to eat as much as they wanted of the high-fructose diet gained 50 percent more weight than the control group.

They developed diabetes at three times the rate of the control group and also developed hepatic steatosis, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

The big question for the researchers was what caused the liver damage. Was it because the animals got fat from eating too much, or was it something else?

To answer that question, this study was designed to prevent weight gain.

Ten middle-aged, normal weight monkeys who had never eaten fructose were divided into two groups based on comparable body shapes and waist circumference.

Over six weeks, one group was fed a calorie-controlled diet consisting of 24 per cent fructose, while the control group was fed a calorie-controlled diet with only a negligible amount of fructose, approximately 0.5 per cent.

In the high-fructose group, the researchers found that the type of intestinal bacteria hadn’t changed, but that they were migrating to the liver more rapidly and causing damage there.

It appears that something about the high fructose levels was causing the intestines to be less protective than normal, and consequently allowing the bacteria to leak out at a 30 per cent higher rate, Kavanagh said.

The study is published online in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.